Long before I dreamed of building my own small business from the ground up — with my hands, heart, and savings — I knew something was deeply off in Kalamazoo. Beneath the surface, something about the way people lived, moved, and were treated just didn’t add up.

And the deeper I looked into the systems around me—housing, justice, and local city governance —the more I realized my experience wasn’t isolated. It was designed. What I’m still living through today is part of a much older pattern: the legacy of Kalamazoo housing discrimination.

But to truly understand how, we have to start at the beginning. Before I tell you my story, you need to hear the one that built the ground we stand on.

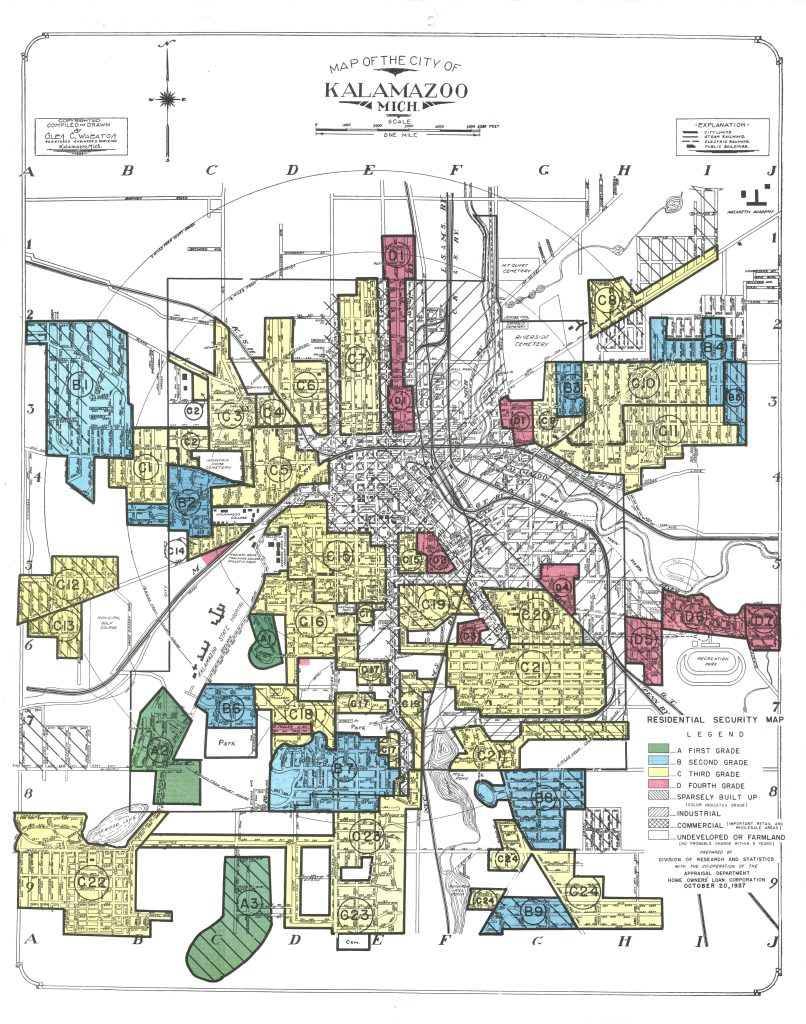

Image featured above: Courtesy of the Kalamazoo Public Library.

Kalamazoo: Two Cities in One

Kalamazoo is often painted as a city full of promise, a place where kids can go to college for free, where creatives thrive, where new development is on the rise.

And yet, walk just a few blocks in the “wrong” direction and you’ll find a different story. Cracked sidewalks. Boarded-up homes. Overpoliced corners. Generational poverty. Housing instability. Fear.

The truth is: Kalamazoo has always been a city divided by race, by class, and by a quiet but powerful system that decided who belongs where.

What Is Redlining?

In the 1930s, the federal government began working with banks to map neighborhoods across the country, labeling them as good or bad investments. This process became known as redlining because the “undesirable” neighborhoods were marked in red on official maps.

“Undesirable” meant predominantly Black, immigrant, or working-class communities, regardless of how well-kept or thriving those areas actually were.

In 1937, Kalamazoo was redlined.

Neighborhoods like the Northside, Edison, and Eastside were outlined in red.

Banks denied loans.

City investment dried up.

Home values plummeted.

And residents, overwhelmingly Black and brown, were cut off from opportunity.

Map Source: Kalamazoo Public Library, Local History Collection

Why This Still Matters Today

Redlining was made illegal in 1968, but its legacy has never been repaired.

Today, those same neighborhoods still:

- Face disinvestment

- Are underdeveloped compared to other areas

- Struggle with outdated infrastructure and poor city services

- Experience housing code enforcement that feels more punitive than protective

- Have residents who are still systemically displaced

The line was erased from the map, but not from policy.

Many residents today, especially renters and low-income families, continue to live within the aftermath of those original red zones.

A System Built to Fail Us

What I’ve come to understand, as someone who tried to build something beautiful in this city, is that the system wasn’t built to support us. It was built to hold us in place.

What was once done through maps and mortgage denial is now done through:

- Discriminatory housing practices

- Ignored code violations

- Unchecked landlord power

- Ineffective or complicit local agencies

- Corrupt or performative city leadership

- What I refer to in my situation as the “HUD hustle game,” where money circulates through government entities and programs that seldom protect the people they are intended to serve.

My Story Is Coming — But First, the Soil I Was Planted In

I didn’t end up in this fight overnight.

Before I ever faced discrimination and retaliation, before I ever filed a complaint, before I realized how deep the silence runs in Kalamazoo — I was just a resident. A dreamer. A builder.

Over a year before I stepped foot into my current housing situation, I started something called Homecrest & Co. It was a labor of love. A small business. A creative vision rooted in care, community, and courage.

I’ll tell you that story next, from the first spark of the idea to what I poured into it with nothing but grit, belief, and late nights.

But I wanted you to know this history first. Because what happened to me didn’t come from nowhere. It came from a system that was never meant to protect me.

A busy downtown scene during construction of the Kalamazoo County Building. US-12 and M-43 signs mark the city’s role as a regional hub.

Photo Credit: Crescent Studios / Kalamazoo Public Library

Coming Up in Blog Post #2

The Birth of Homecrest & Co. — Creating Light in a City That Wanted Darkness

What does it take to start something from scratch when the odds are stacked against you? What does it feel like to invest in hope, only to have the system knock it down?

Next time, I’ll tell you how it all began.

Resources and Further Reading

- MSU Extension: Redlining in Kalamazoo

- Mapping Inequality: HOLC Maps Project

- Bridge Michigan: Redlined Legacy

Legal Disclaimer

This blog is a personal account reflecting the author’s lived experiences, research, and opinions. All information is believed to be accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge. Any references to individuals, agencies, or public officials are based on firsthand experience, publicly available records, or matters of public concern.

This publication is not intended to defame, harass, or misrepresent any person or entity. It is protected speech under the First Amendment and is provided for informational, educational, and advocacy purposes only.

Leave a Reply to Chenaan Eastman Cancel reply